The opening of Erik Rittenbery’s A Vagabond for Beauty recently published on Substack has been dancing in my imagination ever since I first read it:

He was a young man with a craving for the ultimate, a complex man who refused to let his passions loiter in the cesspool of time. He was a wanderer with a poetic soul who danced with his dreams only to be consumed by their flaming embrace.

When that happens, it makes me want to work out why. I shared it with Nina Schuyler of Stunning Sentences on Substack. As we have different approaches, I suggested we do a parallel analysis. I was delighted when she accepted. The link to her post can be found below so you have easy access to both our takes on Erik’s opening.

On repeated reading, two things struck me as powerful about it: the rhythm and the story structure.

The power of rhythm

Firstly, I was struck by the natural flow of the rhythm. I’d just finished a book which told a powerful story in what I felt was an unconsciously jagged way, so I was attuned to this particular aspect of writing.

Even now, I’m struck by the flow of the words. I keep returning to the irregular regularity of the 2-beat metre, a consistent tick-tock pulse overlaid with a jaunty rhythm (the dance itself) which underpins the journey forwards towards the ultimate in an inevitable, ominous, unstoppable drive towards the finish.

He was a young man with a craving for the ultimate,

The opening clause could be read in many ways, all of which fit the 2-beat metre, as the analyses of some of the possible readings show:

This accentual rhythmic treatment is far more interesting than the more regular syllabic ‘The young man craved the ultimate’ (trochaic tetrameter, for what it’s worth):

In ‘A’ and ‘B’, the upbeat or anacrusis of ‘He was a’ which leads to ‘young’ lengthens the vowel sounds in the word. Stress ‘He’, as in ‘C’, ‘D’, and ‘E’; the effect is the same. Within that first clause, the upbeats continue to draw us towards the stressed words: ‘with a’ → ‘craving’ (putting a delicious emphasis and yearning on the drawn-out syllable, emphasising the longing behind it, driving the thought forward), followed by ‘for the’ → ‘ultimate’. Then, a descending tricolon (or series of three) formed by long, medium, and short vowel lengths emerges: ‘young’, ‘craving’, ‘ultimate’. And how poignantly the shortest of these three emphasises the widest term possible: the ultimate.

a complex man who refused to let his passions loiter in the cesspool of time.

This next clause has a single-syllable word anacrusis (‘a’) which leads to ‘complex’:

There’s almost a syncopation in ‘F’, emphasised by the ‘let’ / ‘loiter’ alliteration – both words, incidentally, on unaccented ‘beats’; both verbs. The syncopation echoes the battle between willpower and passions. It’s more subtle than Poe’s dictum of the sound of a line needing to provide an ‘echo to the sense’. Its deep, rich undertone vibrates poignantly to the man’s inner conflict. While ‘G’ lengthens ‘loiter’, it still has a similar effect. The flexibility of Erik’s writing, which lends itself to a number of rhythmic readings while maintaining a constant binary pulse, is masterful.

He was a wanderer with a poetic soul who danced with his dreams only to be consumed by their flaming embrace.

As a new musical line comes in, a new layer appears in the pattern: ‘young’, ‘complex’, ‘wanderer’. Declaim the words alound, and you’ll probably notice how they form an ascending tricolon of 1, 2, and 3 syllables, the first two adjective-noun phrases with the repeated word ‘man’ give way to a single noun, ‘wanderer’. The 2-beat rhythm, however (at least for me) demands that there be a pause after ‘wanderer’:

This pause after ‘wanderer’ further heightens the tension between the active sense of wandering, and the noun which arrests the action, transforming it to a more static quality. While ‘dreams’ and ‘—brace’ are the only beats with single syllables, the ‘young’, ‘complex’, ‘wanderer’ pattern points to the second powerful feature I noticed abour the opening paragraph. This one goes deep.

The power of story structure

I use an example with students to illustrate the demands that rhetorical patterns make on us:

This blanket is yellow. This blanket is fluffy. This blanket is mine.

The content simply doesn’t meet the demands of the form.

Meditate on the meanings of the terms ‘young’, ‘complex’, ‘wanderer’, and you’ll find that these terms do. But they do more than that. They – and the clauses they belong to – not only fit a rising tricolon, they also map to a powerful dynamic story structure: the Revelation structure, one of 18 story structures I describe in my book, Story and Structure. Both are closely linked.

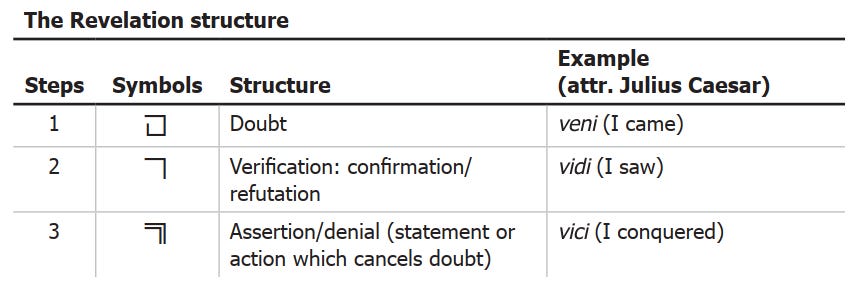

The structure traces ‘a character’s changing state of being in relation to how they perceive their environment.’ The sequence goes from doubt, to verification, and on to either confirmation or denial. Simply put, it follows what I call a ‘veni, vidi, vici’ sequence:

Just as there is doubt (I came because I heard a rumour), followed by verification (I saw with my own eyes), from which decisive action flows, leading to the ultimate conquest, so here, we can trace a similar sequence of events through the opening paragraph of ‘Vagabond’.

But, as Marie Louise von Franz notes, the sequence does not stop at a ‘1, 2, 3’. It’s best thought of as a ‘1, 2, 3 – bang!’ sequence. The ‘bang!’, as story structure reveals, typically marks a shift in register, usually from physical to metaphysical, or vice versa. The implication here being that the man’s life shifts from one plane of existence to another with his (untimely?) death.

If this were an orchestral piece of music, the rhythm could be the percussion section and the sonoroity, the string section. Imagine the Revelation structure as the woodwind section entering. The ‘craving for the ultimate’ presents a sense of doubt or lack (veni). His refusal ‘to let his passions loiter’ shows a rational decision based on his evaluation of the situation (vidi). The ending, however, is tragic (rather than conquering, he was conquered). The inside–outside tension was overthrown by the inner thought–feeling conflict.

The brass section would be the central philosophical question of the passage: What is the quality of a life well lived? There are no easy answers, but it’s a fabulous question to engage with.

You’ll find Nina Schuyler’s analysis of this same opening paragraph on her insightful Stunning Sentences Substack channel here.

I admire the quality of Erik’s writing, and I believe that an appreciation of elements which form the art and craft of writing and and consistent practice to develop mastery of each of them can help this kind of powerful writing to flow. I also believe in the power of our embodied sense of story structure – particularly the two dynamic structures outlined in Story and Structure (the Revelation structure and the Chinese Circular Structure). And there’s much to learn from deepening one’s appreciation of grammar and sentence structure, as Nina shows. By developing an awareness of these approaches, writers can develop their ability to produce lyrical prose.

Try both approaches. See how you get on.